|

|

| ORIGINAL ARTICLE |

|

| Year : 2014 | Volume

: 9

| Issue : 2 | Page : 59-62 |

|

Congenital malformations as seen in a secondary healthcare institution in Southeast Nigeria

CN Onyearugha1, BN Onyire2

1 Department of Paediatrics, Abia State University Teaching Hospital, Aba, Nigeria

2 Federal Medical Centre, Abakaliki, Nigeria

| Date of Web Publication | 19-Aug-2014 |

Correspondence Address:

C N Onyearugha

Department of Paediatrics, Abia State University Teaching Hospital, PMB 7004, Aba

Nigeria

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None  | Check |

DOI: 10.4103/9783-1230.139163

Objective: The aim was to determine the prevalence and pattern of congenital malformations. Materials and Methods: A retrospective study of neonates with congenital anomalies delivered at Federal Medical Centre Abakaliki, Ebonyi state over 10 year period was conducted. Data were extracted from the delivery records of neonates and mothers. Results: The prevalence of congenital anomalies was 0.42%. Highest frequency of congenital anomalies occurred in the digestive system (36.7%), followed by the skeletal system and the least in the cardiovascular system (5%). Majority of cases (83.3%) were term babies while 85% had normal birth weight. Highest proportion of babies with congenital anomalies (35%) was delivered by mothers aged 25-29 years and 40% by those of parities 4, 5. Ninety-three percent of the mothers were booked. Conclusion: The prevalence of congenital malformations in this study was 0.42%.Congenital malformations of the digestive system are the most prevalent in this study. Keywords: Abakaliki, Congenital, Malformations

How to cite this article:

Onyearugha C N, Onyire B N. Congenital malformations as seen in a secondary healthcare institution in Southeast Nigeria. J Med Investig Pract 2014;9:59-62 |

How to cite this URL:

Onyearugha C N, Onyire B N. Congenital malformations as seen in a secondary healthcare institution in Southeast Nigeria. J Med Investig Pract [serial online] 2014 [cited 2018 Aug 24];9:59-62. Available from: http://www.jomip.org/text.asp?2014/9/2/59/139163 |

| Introduction | |  |

Congenital malformation could be defined as any abnormality of structure, function, behavior or chemical composition arising during pregnancy and manifesting at birth or within a few years later. [1] Though congenital malformations are not among the leading causes of perinatal morbidity and mortality in the developing countries as in the developed nations, [2],[3] their prevalence cannot by any means be insignificant. Congenital malformation often becomes a cause for worry and anxiety for expectant parents when their product of conception anticipated with all sense of impending joy and happiness turns out to be abnormal.

In general, congenital malformations occur more commonly in Negroid races than Caucasians probably due to inadequate use of antenatal services, maternal infections and malnutrition occurring more in the former. [4],[5] In up to 40-60% of cases, the cause is unknown. However, identified causes include heredity and environmental factors such as single gene autosomal and sex-linked conditions, maternal infections, malnutrition, irradiation, smoking and use of alcohol, drugs such as anticonvulsants as well as parental advancing age and in vitro fertility procedure. [6],[7],[8],[9]

The burden of disease arising from congenital anomalies can be quite enormous on the family, community and the nation as a whole. Knowledge of the prevalence, types and associated factors makes for better planning and provision of preventive measures where possible as well as treatment and rehabilitation as necessary.

Documented rates of congenital anomalies vary from country to country and even in localities within a country. For instance, rates of congenital malformations noted in Akwa Ibom and Cross River states in the South region and Kano state in the North-East region of Nigeria are 0.4% and 5.8%, respectively. [10],[11] Rates of 0.4% and 0.2% were documented in different localities of Port Harcourt city, in Rivers state. [12] Therefore the more studies done in the process of determining the incidence, the more information obtained and the greater insight gained concerning the incidence and types of anomalies.

There is a paucity of data on congenital anomalies from this state located in the South Eastern region of Nigeria. Hence, the need for the survey.

| Materials and methods | |  |

This was a retrospective study derived from hospital records of Federal Medical Centre (FMC) Abakaliki before its recent merging with Ebonyi State University Teaching Hospital (EBSUTH) to form Federal Teaching Hospital, Abakaliki. As at the time of this study, FMC was a baby friendly secondary healthcare facility located in Abakaliki, the fast growing capital of Ebonyi state which also harbors another secondary health care facility and the then state university teaching hospital, EBSUTH. Its annual delivery rate averaged approximately 1500, whereas the annual pediatric and neonatal admissions were approximately 1331 and 230, respectively.

The records of congenital malformations in the delivery unit of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Special Care Baby Unit (SCBU) of Department of Pediatrics were studied over a 10 years period (from April 1, 2002 to March 31, 2012). The lists of congenital anomalies were compiled and arranged according to systems of the body involved. Other data extracted included the maternal age, parity and booking status as well as the gestational age and birth weight of the baby. The incidence of anomalies was calculated per 1000 births and as percentages of anomalies. Simple proportions were used in the descriptive analysis. For the purpose of the study, congenital anomaly was taken as abnormality of structure or form detectable on physical examination and/or with available, investigational services at birth or within a few days after delivery. Parity of the mother was taken as that prior to the delivery of the congenital baby.

| Results | |  |

There were 14,446 deliveries during the study period with 60 (0.42%) having detectable congenital anomalies. Congenital anomalies were observed in the body systems in descending order of frequency as follows: Digestive system, 22 cases (36.7%), with a prevalence of 1.52/1000 births; skeletal system, 19 cases (31.7%) prevalence, 1.3/1000 births; central nervous system and respiratory system, 8 cases (13.3%), prevalence 0.05/1000 births each and cardiovascular system, 3 cases (5.0%), prevalence 0.02/1000 births as shown in [Table 1].

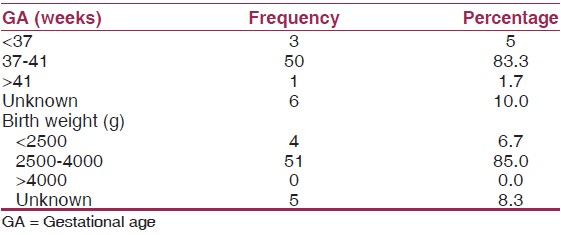

The mean gestational age of the newborns was 38.4 weeks, range 36-42 weeks. Overwhelming majority (83.3%) were term babies as shown in [Table 2].

The mean birth weight of the babies with congenital anomalies was 3100 g, range 2100-3900 g. Eighty-five percent of the babies weighed 2500-4000 g. None was macrosomic [Table 2]. | Table 2: Birth characteristics of newborns with congenital malformation

Click here to view |

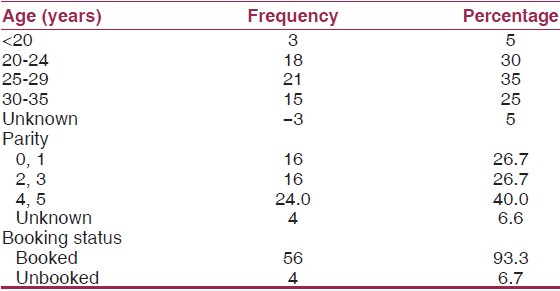

The mean maternal age was 26.4 years, range 18-35 years. Highest proportion of the mothers (35%) was aged 25-29 years. Teenage mothers were the least in number (5%), as shown in [Table 3]. | Table 3: Maternal characteristics of newborns with congenital anomalies

Click here to view |

Mothers of higher parities, 4.5 (40%) had the higher incidence of deliveries of babies with congenital malformations than those of parities lower parity [Table 3].

Overwhelming majority (93.3%) of the mothers was booked.

| Discussion | |  |

The prevalence of congenital malformations in this study was 0.42%. This being a hospital study conducted in a tertiary health care facility; the value is very much likely to be less than the real magnitude of the problem in the community. A large percentage of pregnancies are unsupervised with deliveries taking place in traditional birth attendants' facilities, homes and spiritual places of worship due to ignorance, poverty and negative cultural beliefs. [13],[14],[15] As a result, many cases of congenital anomalies are not documented.

The prevalence of congenital malformations in this study is similar to that obtained from a teaching hospital in Port Harcourt located in oil-rich Rivers state of Nigeria [12] where communities are frequently exposed to environmental pollution from uncontrolled gas flaring and oil spillage. The similarity is not readily explicable. It might be for the reason of both being studies of obvious congenital anomalies delivered in teaching hospitals in adjacent geopolitical zones of Nigeria.

However, the result obtained in this work is much <5.5/1000 births obtained in Kano, [11] North-East zone and 15.8/1000 births obtained in Lagos, [16] South-West zone of Nigeria. The reasons for the wide variations in the results might be for over 90% of the population in the Kano study comprising Hausa-Fulani ethnic group noted for consanguinity of marriage possibly predisposing to increased rate of congenital malformations of genetic origin. [17],[18] The highly multi-ethnic and industrial nature of Lagos possibly results in increased rates of anomalies of genetic and environmental origin from consanguineous marriages and exposure to pollution from industrial wastes respectively. [18],[19],[20],[21]

The highest prevalence of congenital anomalies was recorded in the digestive system. This is similar to the observations in studies conducted in Abia State University Teaching Hospital Aba, Abia State [4] in the same geopolitical zone as our study center and Kano in Kano State, [11] North-Eastern zone of Nigeria. In contrast, central nervous system anomalies were the most frequent congenital anomalies recorded in studies carried out in Akwa Ibom, Rivers and Lagos states of Nigeria. [10],[12],[16] This difference in the body systems manifesting most frequent malformations in the different locations of the country aforementioned is not readily explainable. However, our study center, Abia, and Kano states reporting highest anomalies in the gastrointestinal tract are located in the hinterland of the country unlike rivers, Akwa Ibom and Lagos states showing most frequent anomalies in the central nervous system which are coastline oil-rich states with their populations suffering frequent exposure to environmental pollution from hydrocarbons and their compounds resulting from frequent oil spillage and uncontrolled gas flaring as well as from the activities of petrochemical industries located in these areas. Pollution from the petrochemical industries has been reported as causing birth defects. [19] Toxic agents might affect particularly the development of the central nervous system which occurs in the 4 th and 5 th weeks of gestation. [22]

Most (83.3%) of the congenital malformations were seen in full term newborns. This may be explained by the fact that congenital malformations when occurring in preterm babies delivered in our study center might not be quite obvious and, therefore, possibly missed by the nursing staff and less experienced doctors who usually attend normal deliveries.

Overwhelming majority (85%) of the newborns with congenital malformations were of normal birth weight because most of the malformations recorded in this study except cardiovascular system disorders occurred in body systems or areas not ordinarily associated with low or high birth weight.

The mean age of mothers of babies with congenital malformations is 26 years, while mothers in 24-29 years age bracket had the highest prevalence of congenital malformations. The lower mean maternal age recorded in this study than some previous ones could be due to our study population being younger with age range of 16-35 years while those of Enugu [23] and Lagos [16] had age ranges of 20-39 years and 18-39 years respectively. The highest prevalence of congenital malformations occurring in mothers aged 24-29 years in this study could be explained by the fact that this is the age bracket with high parity rates. [4],[5] Congenital malformations have been noted previously as occurring most frequently in women with high pregnancy rates. [2]

Overwhelming majority (93.3%) of the mothers in this survey were booked. However, the paucity of documentation in the case notes including the time of booking has denied the authors the ability to evaluate the possible effect of time of booking on the prevalence of congenital anomalies observed in this study. It is known that delayed booking (which is common in developing countries including Nigeria) [24],[25] often denies expectant women the due prescription and intake of folic acid and vitamins known to be preventive of neural tube defects when administered in the periconceptional period. [26]

| Limitations | |  |

This being a retrospective study lacks the purposeful alertness to scrutinize all the deliveries to identify all cases of congenital malformations as would have been the case in a prospective study. Hence some congenital anomalies might possibly have been missed further limiting the prevalence even as might have manifested in the hospital. It would have been appropriate to evaluate the contribution of congenital anomalies to perinatal morbidity and mortality in this study, but for the unavailability of adequate data due to insufficient and missing documentations from the case notes.

| Conclusion | |  |

The prevalence rate of congenital malformations in this study was 0.42%. Congenital anomalies of the digestive system are the most prevalent malformations in this study.

| Acknowledgment | |  |

We express profound gratitude to the staff of SCBU and Medical Records Department for their cooperation and assistance in the process of conducting a survey.

| References | |  |

| 1. | Collins P, Billets FC. The terminology of early development history, concepts and current usage. Clin Anat 1995;8:15-48.

|

| 2. | Ambe JP, Madziga AG, Akpede GO, Mava Y. Pattern and outcome of congenital malformations in newborn babies in a Nigerian teaching hospital. West Afr J Med 2010;29:24-9.

|

| 3. | Turnpenny P, Ellard S. Congenital abnormalities. Emery's Elements of Medical Genetics. 12 th ed. Edinburgh: Elseviers-Churchill Livingstone; 2005. p. 1-5.

|

| 4. | Ekanem TB, Incidence of congenital malformation in the maternity section of Abia State University Teaching Hospital (ABSUTH) from 1984 to 1999. J Exp Clin Anat 2004;39:31-3.

|

| 5. | Hudgins L, Cassidy SB. Congenital anomalies. In: Martin RG, Fanroff AA, Waish MC, editors. Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine. 8 th ed. Philadephia: Mosby-Elsvier; 2006. p. 561-81.

|

| 6. | Rottlaender D, Hoppe UC. Risks of non-prescription medication. Clobutinol cough syrup as a recent example. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2008;133:144-6.

|

| 7. | Stoll BG. Congenital anomalies. In: Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, Behrnan RE, Staton BF, editors. Nelson Textbook of Paediatrics. 18 th ed. Philadephia: WB Sanders Co.; 2008. p. 711-13.

|

| 8. | Malla BK. One year review study of congenital anatomical malformation at birth in Maternity Hospital (Prasutigriha), Thapathali, Kathmandu. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2007;5:557-60.

|

| 9. | Sadler TW. Birth defects. In: Sadler TW, Langman J, editors. Langman's Medical Embryology. 9 th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincot Williams and Wilkins; 2004. p. 149-58.

|

| 10. | Ekanem TB, Okon DE, Akpantah AO, Mesembe OE, Eluwa MA, Ekong MB. Prevalence of congenital malformations in Cross River and Akwa Ibom states of Nigeria from 1980-2003. Congenit Anom (Kyoto) 2008;48:167-70.

|

| 11. | Mukhtar-Yola M, Ibrahim M, Belonwu R. Prevalence and perinatal outcome of obvious congenital malformations among inborn babies of Aminu Kano University Teaching Hospital, Kano. Niger J Paediatr 2005;32:47-51.

|

| 12. | Ekanem B, Bassey IE, Mesembe OE, Eluwa MA, Ekong MB. Incidence of congenital malformation in 2 major hospitals in Rivers state of Nigeria from 1990 to 2003. East Mediterr Health J 2011;17:701-5.

|

| 13. | Lamina MA, Suleadu AO, Jagun EO. Factors militating against delivery among patients booked in Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital Sagamu, Nigeria. Niger J Med 2004;13:52-3.

|

| 14. | Etuk SJ, Etuk IS. Relative risk of birth asphyxia in babies of booked women who deliver in unorthodox health facilities in Calabar, Nigeria. Acta Trop 2001;79:143-7.

|

| 15. | Ezechukwu CC, Ugochukwu EF, Egbuonu I. Chukwuka JO. Risk factors for neonatal mortality in a regional tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2004;7:50-2.

|

| 16. | Iroha EO, Egri-Okwaji MT, Odum CU, Anorlu RI. Perinatal outcome of obvious congenital malformations as seen at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital. Niger J Paediatr 2001;28:73-7.

|

| 17. | Rajangam S, Devi R. Consagunity and chromosomal abnormality in mental retardation and or multiple congenital anomalies. J Anat Soc India 2007;56:30-33.

|

| 18. | Sorouri A. Consanguineous marriage and congenital anomalies. Isfahan Univ Med Sci 1980;1:1-15.

|

| 19. | Oliveira LM, Stein N, Sanseverino MT, Vargas VM, Fachel JM, Schuler L. Reproductive outcomes in an area adjacent to a petrochemical plant in southern Brazil. Rev Saude Publica 2002;36:81-7.

|

| 20. | Ritz B, Yu F, Fruin S, Chapa G, Shaw GM, Harris JA. Ambient air pollution and risk of birth defects in Southern California. Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:17-25.

|

| 21. | Vrijheid M, Dolk H, Armstrong B, Abramsky L, Bianchi F, Fazarinc I, et al. Chromosomal congenital anomalies and residence near hazardous waste landfill sites. Lancet 2002;359:320-2.

|

| 22. | Czeizel AE, Puhó EH, Acs N, Bánhidy F. Use of specified critical periods of different congenital abnormalities instead of the first trimester concept. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2008;82:139-46.

|

| 23. | Obu HA, Chinawa JM, Uleanya ND, Adimora GN, Obi IE. Congenital malformations among newborns admitted in the neonatal unit of a tertiary hospital in Enugu, South-East Nigeria-A retrospective study. BMC Res Notes 2012;5:177.

|

| 24. | Gharoro EP, Okonkwo CA. Changes in service organization: Antenatal care policy to improve attendance and reduce maternal mortality. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1999;67:179-81.

|

| 25. | Ogunlesi TA. The pattern of utilization of prenatal and delivery services in Ilesa, Nigeria. Internet J Epidemiol 2005;2.

|

| 26. | Smithells RW, Sheppard S, Schorah CJ, Seller MJ, Nevin NC, Harris R, et al. Apparent prevention of neural tube defects by periconceptional vitamin supplementation. Arch Dis Child 1981;56:911-8.

|

[Table 1], [Table 2], [Table 3]

|