Consciously or subconsciously, this cry [for balance] refers to Spiritualism: this science that alone will be able to accomplish a reconciliation between head and heart, to restore the balance between moral and intellectual development, because it demonstrates to humanity the spirituality of the soul

—W.H.C. Tenhaeff, (1919).1.

Introduction

Spiritualism revolves around the conviction that death is not the end of our being. This was not solely a religious or ideological persuasion. Spiritualists did not merely believe in survival after death; they were convinced they had empirical proof. Through mediums, the deceased were believed to manifest themselves during séances either by conveying written and spoken words or by moving objects.2 Everyone present at a séance could witness for themselves the reality of these phenomena.

In its emphasis on proof, spiritualism was at the foundation of the science of psychical research and – later on – parapsychology. Scientific psychical research began in 1882 when the British Society for Psychical Research (BSPR) was established by eminent scholars such as Frederic Myers, William Barrett and Henry Sidgwick. Other countries soon followed.3 In the Netherlands, critical psychical research would take until 1919 to emerge, when the Studievereeniging voor Psychical Research (SPR) was established, with the philosopher and first Dutch professor in psychology Gerard Heymans as its president. In this article we consider that it was no coincidence that the Dutch SPR was founded shortly after the First World War ended.

The heyday of spiritualism is usually placed between the 1860s and the 1880s, but spiritualism experienced a revival during the First World War – especially in the United Kingdom.4 The argument used by most authors for this revival is mass bereavement,5 and one can easily imagine that with the loss of so many young men, people were looking for solace. Séances seemed appealing, as the mourning were promised they would be able to communicate with their deceased loved ones.6 However, mass bereavement does not seem to provide a sufficient explanation. Even in the Netherlands, a country that did not suffer such direct losses, spiritualism gained momentum during the First World War. How do we interpret this revival of Dutch spiritualism during the First World War, and how does it relate to the emergence of the Dutch SPR in 1919? In order to answer these questions, we will discuss the characteristics of Dutch spiritualism before, during and after the war.

Spiritualism before the First World War

The movement of spiritualism originated in the United States in 1848, when the Fox sisters claimed to communicate through raps with a deceased person in their cellar. The sisters received widespread attention from the press. Spiritualism crossed over to the United Kingdom and reached the Netherlands in the late 1850s through the travels of the famous Scottish medium Daniel Douglas Home (1833–1866).7 Encouraged by his Dutch acquaintance baron Johannes Nicolaas Tiedeman Martheze, Home held in 1858 ten séances on Dutch soil. Four of these took place at the palace of Queen Sophie, whose deceased son was said to have appeared during one séance. Home’s séances received ample coverage in Dutch magazines and newspapers.8 Spiritualism became part of what Jan Romein notoriously deemed the ‘small religions’, referring to pacifism, anti-vivisectionism and other esoterically oriented new religious movements.9

As a result of the Netherlands’ central position in Europe, surrounded as it was by the United Kingdom, Germany and France, several different strands of spiritualism developed. Scholars have made several distinctions between these varieties of spiritualism in the Netherlands.10 In his study on the nineteenth-century Protestant clergy and their spiritualist opinions, historian Derk Jansen distinguishes ‘Christian spiritualists’ from ‘modern spiritualists’. According to Jansen, indisputable scientific proof of the spirits’ manifestations was crucial to modern spiritualists. He identifies this variety of spiritualism in the very first Dutch spiritualist organisation of Oromase (1859–1860), later resurrected as Oromase II (1868–1879).11

However, Jansen is most interested in Christian spiritualists: the spiritualists who utilised manifestations of spirits to validate their Christian convictions about God and Jesus.12 Elise van Calcar (1822–1904) was one of the most ardent advocates of this popular interpretation of spiritualism in the Netherlands. Van Calcar is usually remembered as an author, child psychologist and feminist, although she herself had believed that her spiritualist work would be most noteworthy. From 1873 onwards she dedicated her life to spiritualism. She was a devoted Christian and was convinced that spiritual manifestations would help strengthen the Protestant Church.13

Art historian Marty Bax has contested the distinction made by Jansen, stating that all spiritualists upheld a Christian world view and used scientific discourse.14 She claims that Christian spiritualists fiercely opposed the idea of reincarnation. Reincarnation spiritualism was represented in the Netherlands most actively by members of the society Veritas (1869-ca. 1937), established in Amsterdam. Famous Dutch author Hendrik Jan Schimmel (1823–1906) was one important proponent of this brand of spiritualism in the Netherlands. It was referred to by its French term ‘spiritism’, as coined by the Frenchman Allan Kardec.15

Indeed, reincarnation was the topic of heated debate for Dutch spiritualists, who several times tried to reconcile their differences. One of the most successful attempts was the establishment of De Spiritistische Broederbond Harmonia in 1888, which aimed to unite the various spiritualists regardless of their specific denomination. This first national spiritualist organisation had the goal to ‘enhance the love, peace, consensus between spiritists and spiritualists’.16

Historian Jansen believes that with the establishment of Harmonia, Christian spiritualism came to an end and would experience only a short revival in the activities of the Evangelical preacher Martinus Beversluis.17 We will demonstrate, however, that even after 1888 and during the First World War, Dutch spiritualism was to a large extent an ideological movement, much more so than a critically scientific one. In this regard, we adhere to the distinction Leonieke Vermeer has made in her research on Dutch spiritualism around 1900.18 We believe that a valuable distinction can be made between ideological and critical spiritualists, suggesting an explanation as to why Dutch psychical research emerged shortly after the First World War.

This distinction is exemplified par excellence by the Harris incident, recounted below, on the eve of the First World War. In the exposure of a fraudulent medium, critical spiritualists succumbed to their ideological counterparts, demonstrating the dominance of the latter. It was this dominance that had ever since the 1850s severely halted the development of Dutch psychical research.19

The Harris incident

The American ‘trumpet medium’ Susanna Harris (1854–1932) claimed to convey the voices of spirits through a big trumpet. On 16 April 1914 Harris performed a séance in Amsterdam. Some spiritualists present were not convinced of the validity of her claims and decided to put her to the test on the spot. Harris used three trumpets and in the darkened room one of the attendants crawled across the floor to take away one of them. Neither Harris, nor the alleged spirits noticed the missing trumpet. The sceptical spiritualist called her out in the middle of the séance: surely the spirits should have alerted the medium that one of her trumpets was missing! After all attendants had discussed the events in a back room, they decided to let the séance continue. Unfortunately, Harris had already disappeared with her assistant and the entrance fees.20

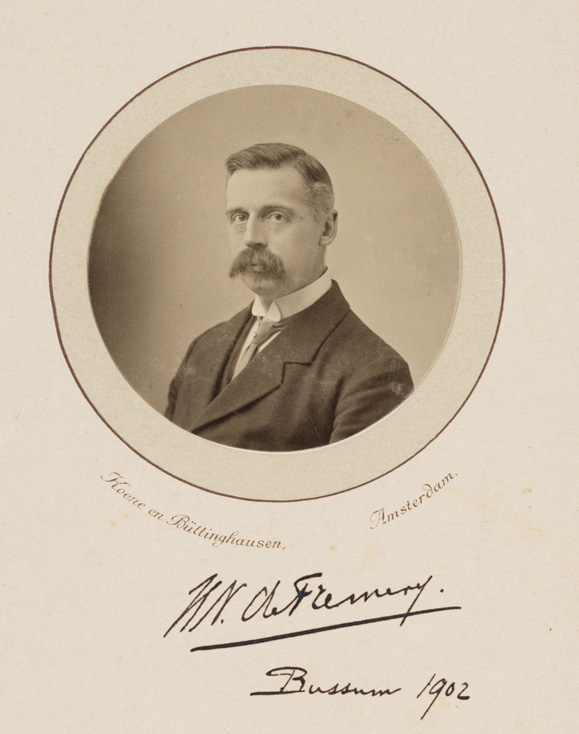

These events caused a huge commotion, especially since one of the most eminent Dutch spiritualists – Henri de Fremery (1868–1940) – supported the allegations of fraud. De Fremery came from a noble family and after his career as an artillery officer was able to devote himself to spiritualism full-time. De Fremery was one of the co-founders of Harmonia and well-respected in spiritualist circles. The Harris incident exposes the divide between De Fremery as a ‘critical’ spiritualist and his opponents, who were more ideologically oriented.fg001

Before 1914, only a handful of Dutch spiritualists had been interested in critically examining spiritual manifestations. The first was the physician and author Frederik van Eeden (1860–1932), who regarded the investigation of spirits as a necessary part of the pioneering discipline of psychology.21 However, by the time the First World War started, Van Eeden had converted to Catholicism and moved away from spiritualism. The vitalist Floris Jansen (1881–1937) had been working together with Henri de Fremery from 1904 to 1906 to study the existence of a spiritual fluid in a laboratory,22 but in 1914 Jansen had long moved to Argentina. Marcellus Emants (1848–1923) had been trying at various times – unsuccessfully – to initiate a Dutch Studievereeniging voor Psychical Research.23 He only half-heartedly defended De Fremery during the Harris incident.24

More ideological oriented spiritualists – such as Pieter Goedhart and J.S. Göbel and G.A.W. van Straaten – believed that De Fremery had seriously harmed the spiritualist movement. They straightforwardly expressed these opinions in their spiritualistic journal Toekomstig Leven, halfmaandelijks tijdschrift gewijd aan de Studie van het Spiritisme en aanverwante verschijnselen, of which De Fremery was one of the editors.25 These three spiritualists claimed that it was not up to De Fremery to decide what counted as proof and blamed him for harming the sensitive medium Harris. De Fremery, on the other hand, was of the opinion that it was the job of the spiritualists to regard the mediumistic séances critically and to study the phenomena seriously. De Fremery was disappointed with his fellow spiritualists’ reactions and withdrew from spiritualism.26 With his withdrawal, critical spiritualism in the Netherlands came to a temporary end. It is typical for Dutch spiritualism before the war that a critical spiritualist such as De Fremery felt he had to succumb to the more ideological spiritualists: he was a minority in a field dominated by ideologically inclined spiritualists.

Harris’ supposed fraud undermined spiritualists’ public reputation. In the press the gullibility of spiritualists and their mutual bickering were expatiated upon.27 Dutch spiritualists were in need of something that would unite them and give them credibility. The outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 appeared to provide just that.

Dutch spiritualism during the First World War

In the Netherlands spiritualism regained attention and recognition during the First World War: the number of Harmonia members grew from at most 630 in January of 1915 to an estimated 1160 members in January of 1919.28 As the Dutch people did not directly experience loss of family members, mass bereavement cannot possibly explain this increase. Dutch spiritualists were divided on whether it would be a good idea to have séances in this time of turmoil – after all, evil spirits might be summoned inadvertently.29 Even so, they agreed that these experiences would convince more and more people of the reality of spiritualism.30

Morality made the war an important subject for Dutch spiritualists, even when they were not themselves victims, because ‘[a] spiritualist mourns for all deaths of all nations’.31 These were the words of Cornelia Johanna Kuijper van Harpen (1864–1927), one of the most outspoken spiritualists on the First World War. She was the wife of Rudolph Otto van Holthe tot Echten (1854–1945), a lawyer and spiritualist who in 1914 tried to legalise the healing practices of magnetisers.32 The Christian spiritualist couple were close friends with Elise van Calcar.33

Like Kuijper van Harpen, two other spiritualists associated with Van Calcar were outspoken about the First World War. They were Martinus Beversluis (1856–1948) and Jacobus Johannes van Broekhoven (1867–1930). Beversluis – perceived by historian Jansen as the embodiment of a short revival of Christian spiritualism – was a pastor and had been a student of Van Calcar from 1886 onwards, until he founded the spiritualistic society Excelsior in 1900. Van Calcar did not favour any form of organisation and was of the opinion that Christian spiritualism should be reserved for insiders only.34 Van Broekhoven was an evangelist working in a small town in Zeeland, a southern province of the Netherlands. He, too, was in close contact with Van Calcar until she died in 1904.35 Both their senses of indebtedness to Van Calcar is reflected in several articles.36 Their dominance in writing about the First World War demonstrates that an ideologically oriented Christian spiritualism had certainly not ended when Harmonia was established in 1888.

These three spiritualists were published extensively in three different journals. While the most prominent was Toekomstig Leven, Beversluis and Van Broekhoven also founded their own spiritualist journals. In 1899 Beversluis began publishing Geest en Leven, tijdschrift gewijd aan de empirische theologie en christelijk spiritualisme (1899–1941) and in 1913 Van Broekhoven started Stemmen uit Hooger Wereld, maandblad gewijd aan de kennis van het eeuwig leven (1913–1930) to address a wider audience with a less expensive journal. From 1914 until 1918 these three journals were the most important channels for Dutch spiritualism.

The three spiritualists put forward a joint consensus proclaiming a strict neutrality on the war. Dutch spiritualists were to choose the higher moral ground and firmly refuse to pick sides in the war. To true spiritualists, the whole war was useless: nobody would benefit from either side winning. The spiritualists’ agreement on the matter was expressed in Van Broekhoven’s single-page article ‘Spiritualism against the War: a word to all like-minded souls’ written on 1 December 1914. The article was printed in all three journals and warmly supported by its editors.37 Van Broekhoven presented four points in his ‘Spiritualism against the War’ that all Dutch spiritualists were able to agree on in their relation towards the First World War. His first point was that God and war were irreconcilable; the second that the war was caused by materialism; the third was that the war could pave the way for a hopeful spiritual evolution and, finally, that an active protest against the war was necessary. These four points will be discussed below in the context of a continuing fin de siècle. Usually the fin de siècle is referred to as the time period that ended with the outbreak of the First World War. However, the way in which spiritualists and related neo-religious movements reacted to the war was very much in the vein of their fin-de-siècle roots.

Decadent materialism

For a long time the fin de siècle has been portrayed as decadent and pessimistic.38 Cultural life at the end of the nineteenth century was believed to be dominated by a feeling of anxiety and worry. There was a growing fear that, as the end of the century came closer, nineteenth-century liberal values such as a belief in progress and rationalism would meet their end. Instead, a feeling of fatalism emerged and the conviction grew that the very foundations of society were being threatened by ‘decadents’. The decadence society feared was felt to be expressed by deviant sexuality, artists who were deemed crazy, a shameless youth and growing anti-Semitism. Also, the increasing number of ‘nervous’ people seemed to confirm the image of a disintegrating society. Anxieties about these developments were expressed mainly in literature and the arts, but also in the various sciences.39

This negative interpretation of modern times was also present among Dutch spiritualists during the First World War. Dutch spiritualists blamed fallible human nature for the horrors of war. This was posited most often by Kuijper Van Harpen. Spiritualists saw the war as a culmination of materialism – greed, self-interest, conceit and all their negative effects.40 In this regard, materialism and therefore the war could seriously harm ‘the spiritual progress of humanity’.41 The war was seen by the spiritualists as a ‘horrifyingly materialistic pathological process’ and was a ‘natural consequence of the central pursuit of our society’.42 The mistake everyone seemed to make, they argued, was that no one realised that a human being is an eternal and immortal creature. Wanting to obtain all sorts of materialistic gain was entirely useless, and the war had been caused by precisely these spiritual shortcomings of the human race.43 For the spiritualists, however, this did not mean there was no hope to be found. Once people understood their own fallible nature, war could come to an end.44 This hopeful message can also be understood in the context of a continuing Dutch fin de siècle.

A hopeful message

The rather pessimistic image of the fin de siècle has been contradicted in recent decades. In this new image, positive elements of the fin de siècle are paid significantly more attention. A fragmented society could, for example, also be interpreted as an invitation for a grand reform. Following the ‘warm meliorism’ that according to the American historian Carl Schorske is typical for artists and intellectuals in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands were also driven to an important degree by a belief in humanity’s potential for improvement.45 Unlike other countries, the Netherlands did not have to recover from a war, its population grew steadily, and its economy thrived.46 Of course the Netherlands had their pessimistic intellectuals, like the ‘Tachtigers’ Willem Kloos or Lodewijk van Deyssel. Nevertheless, these intellectuals were a minority. Dutch spiritualism during the First World War provided an optimistic perspective, which was especially appealing in a period when traditional religion fell short.

As Robbert Striekwold demonstrates in his contribution to this special issue, the churches were struggling to accommodate the First World War in their world view. The idea that war was God’s way of punishing a people was firmly grounded in the Old Testament. This fact made a straightforward condemnation of the tragedies of the war difficult for the Protestant churches.47 The spiritualists provided a viable alternative, since they believed they could prove that war and God had nothing to do with each other. Van Broekhoven: ‘We have looked more deeply into the meaning of being human. The immortality of the human mind is to us no longer an article of faith, but a fact, a fact of experience’.48 Van Broekhoven induced from these facts of experience that all humans mattered and that every individual held an important place in the universe.49 He continued: ‘When will the world, no, when will the Church finally understand that God has nothing to do with war, that the notions of war and God completely exclude each other?’50 Even if the Church could not, spiritualists were able to offer a clear and rational disapproval of the First World War.

Along with this alternative, spiritualism also offered hope for the future. The spiritualists were convinced that the war could be a step forward in the evolution of mankind.51 Van Broekhoven phrased the task of spiritualists as follows: ‘[…] to guide humanity from the darkness of barbarism to the light and freedom of a better day’.52 A spiritualist evolution was at hand: ‘These dark years of blood and tears will pass and a new world will rise from the debris of the old, a world in which nations will come closer together, in which more appreciation for each other will exist, in which right and justice will fly their colours. He who has had a glimpse of the delightful, great potential of humankind, of the eternal, godly principle that is part of its being, he cannot dread or despise the future of the world’.53 Spiritualists attributed significant meaning to a seemingly pointless war. The First World War provided a necessary stop on a materialistic route in order to make way for some serious spiritual evolution.

Words into action

Materialism as a cause of war, spiritualism as a substitute religion and the hopeful perspective of a spiritual evolution are all themes reminiscent of the fin de siècle. For spiritualists and other related neo-religious groups54 the First World War provided a perfect legitimisation of their endeavours. Themes and questions that preoccupied the minds of intellectuals at the end of the nineteenth century had hardly changed at the beginning of the First World War. Especially in the face of something as utterly meaningless as this war, a meaningful interpretation was very attractive. The spiritualists provided this by claiming that the war would help in annihilating the root of all evil – materialism – and eventually lead to a new society in which truly higher morals would be supported worldwide. Spiritualists also put their words into action. Van Broekhoven called for protest in his one-page article:

Spiritualists from all countries must unite in respectable and eloquent protest, a protest that will show the foundations of our unconditional condemnation […]. This protest should be signed by prominent representatives of spiritualism in all countries, and sent to all governments and all prominent magazines, so the whole world can know that millions of people during these dark days hold on to a belief in mankind’s ideal aspects and a better future. Such a protest should provoke many to think and feel ashamed.55

In December 1914 Harmonia joined the Nederlandsche Anti-Oorlograad (NAOR). The NAOR was one of the most active and important anti-war organisations in the Netherlands and was foremost interested in ceasing hostilities and creating conditions for international peace.56 The NAOR went from 8,500 members in 1915 to nearly 39,000 members in 1918.57 With the merger of Harmonia about 500 members were added.58 In their call for peace, the previously much divided Dutch spiritualists were harmonised, which improved their reputation and gained them more active members.59

The modern concerns usually ascribed to the fin de siècle should be interpreted as fears that occupy the human mind in a seemingly meaningless world. As well as a yearning to communicate with those who died in the trenches, this context further explains the revival of spiritualism during those especially confusing years of the First World War – even in a neutral country such as the Netherlands.

Spiritualism after the First World War: psychical research

Before the First World War, Dutch spiritualism was largely ideological, exemplified by the Harris incident and the shutting out of De Fremery and his fellow critical spiritualists. During the First World War, ideologically oriented spiritualists still dominated the spiritualist field in the Netherlands. In their plea against materialism and their call for a spiritual evolution, Dutch spiritualists were certainly not anti-scientific, but they anticipated a different scientific foundation of spiritualism. After the war it seemed that this new variety of science could be emerging.

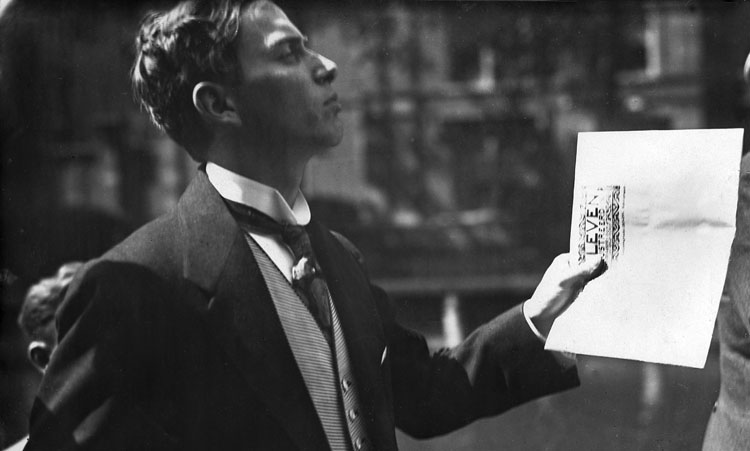

In June and July of 1919 a telepath visited the Netherlands. The performances of this Eugene de Rubini (see fig. 2) reanimated a vivid public debate about the reality of alleged spiritualistic and telepathic phenomena.60 Audiences and scholars alike wondered whether De Rubini was truly capable of locating hidden objects by reading the minds of the people who had hidden them or that he just read their minuscule sensory cues.61 The consensus was that without any proper research, this question was impossible to answer. It was during the discussion about De Rubini’s abilities that the physician Israël Zeehandelaar called for the establishment of a Dutch Society for Psychical Research.

De Rubini had paid Zeehandelaar a visit at his workplace, the Gemeentelijke Geneeskundige en Gezondheidsdienst in Amsterdam, for a demonstration. Although Zeehandelaar was impressed by ‘the simplicity, the lack of adornment, the sincerity of Rubini’, he was not convinced by his telepathic abilities.62 Zeehandelaar believed that De Rubini simply read the involuntary muscle movements of his spectators, but he was still sure it would be the most important scientific endeavour ever to prove the existence of telepathy once and for all: ‘We can only say that the discovery of telepathy as an indisputable natural phenomenon will prove to be of the greatest importance for human society’. Zeehandelaar situated this scientific investigation of telepathy specifically in the context of the First World War: ‘Slowly we all tire of the soulless culture that has found its culmination in the construction of enormous tools of destruction. We have to start discovering the soul and its extraordinary qualities’.63 Thus, in the light of the horrors of war, a new science of the soul was necessary. To make this happen, Zeehandelaar called for the establishment of ‘[…] a Dutch Society like the S.P.R’.64

On 4 October 1919 the Dutch SPR was officially established. The first board of 24 people was an interesting combination of established scholars as well as spiritualists. The psychologist Gerard Heymans was its first president.65 Other psychologists on the board included Henri Brugmans and Frans Roels. Several physicians were among the first members of the board: besides Zeehandelaar, they were Enno Wiersma, Gerbrandus Jelgersma, Johannes van der Hoop and Jan Egbert Gustaaf van Emden. Furthermore, four theologians joined the first board: H.C. van Wijngaarden, Karel Hendrik Roessingh, Hermanus Ysbrand Groenewegen and Gerrit Jan Heering. The teachers and child psychologists Gerardus van Wayenburg, Frederik van Raalt and J.C.L. Godefroy also became members of the board. Then there were the philosophers Leo Polak and Johannes Diderik Bierens de Haan, the authors Nico van Suchtelen and J.A. Schröder, and the two female members, Steens-Zijnen and Boumans-Rutel. Contrary to the United Kingdom, in the Dutch SPR natural scientists were hardly represented: the only exception was the last member, astronomer Jacobus Kapteyn, whose friendship with Heymans prompted him to support the cause.

The spiritualists’ support was represented by the presence on the board of Beversluis and De Fremery. Simultaneously with Zeehandelaar in August of 1919 Pieter Goedhart – one of the fiercest opponents of De Fremery during the Harris incident – had published in Toekomstig Leven a call for the establishment of a Dutch SPR. When he heard of Zeehandelaar’s activities, he encouraged his fellow spiritualists to join Zeehandelaar in this good cause.66 Sound knowledge of spiritual manifestations was necessary, and ‘above all such a society is preferable to facilitate a better and more just appreciation of each other’s points of view’.67

In 1914 a critical appreciation of spiritual phenomena was not welcome, as is evidenced by the Harris case. By 1919 this had changed. Because of the First World War, spiritualism was on more solid ground and able to withstand greater openness to critical scrutiny. Furthermore, in the aftermath of the First World War and in the entire interbellum period, the academic context supported the development of psychical research. In contrast to earlier times there was profound academic interest and involvement in a Dutch SPR.68 What was it that specifically made these scholars willing to participate in the SPR?

A shared interest

The 24 first members of the board of the Dutch SPR shared an optimistic interpretation about the nature of the unconscious. In 1917 the Dutch psychoanalytic society was established with Van Emden and Van der Hoop as two of its founding members. Jelgersma, too, was interested in psychoanalytic ideas, as were the classic scholar Schröder and the child psychologist Van Raalte. The theologian Van Wijngaarden was inspired by concepts out of psychoanalysis and the author Van Suchtelen wrote a popular book about the implications of these specific ideas on the subconscious.69 In its emphasis upon the uncontrollable and potentially destructive powers of the unconscious, Freud had not been very positive about the fundamental human nature. His student Carl Gustav Jung was much more positive, which is perhaps best exemplified by his notion of the ‘collective unconscious’. This can be regarded as a way of symbolic knowing in every individual which transcends the intellect. Jung believed this unconscious shared knowledge should be incorporated for well-being: ‘It is only possible to live the fullest life when we are in harmony with these symbols; wisdom is a return to them’.70 The scholars mentioned above, both interested in psychoanalytic thought and psychical research, shared a more Jungian positive interpretation of the unconscious.71

It is hard to distinguish any profound interest in psychoanalytical ideas in the work of Heymans.72 However, in his own philosophical system of ‘psychic monism’ we recognise a similar hopeful perspective on the unconscious. Zeehandelaar and Kapteyn shared his assumption that: ‘as far as our data reach, only the psychical exists, since everything physical is nothing more than how the psychical is perceived (through interferences which themselves belong to physical processes of perception)’.73 In this philosophy, which Heymans derived from German philosopher and psychologist Gustav Fechter, he presupposed the existence of a ‘world consciousness’ in which the individual consciousness was only partly and temporarily separated from a universal, shared one. For Heymans, the existence of telepathy could demonstrate the reality of his psychic monism. He understood telepathy as an equivalent of suddenly remembering something previously forgotten. When one normally remembers something, an unconscious thought suddenly becomes conscious. Since Heymans believed in the existence of a shared unconscious, he saw no reason why it would not also be possible to suddenly remember someone else’s thought. To study these ‘occult phenomena’, as Heymans called them, the help of the spiritualist members was necessary. They were the ones who would report the phenomena and could bring in the mediums to examine telepathy.74

In contrast to 1914, in 1919 spiritualists were happy to engage in scientific and therefore critical research of spiritual phenomena. After the war the united spiritualists shared their hopeful perspective of an emerging spiritualistic world with the more geisteswissenchaftlich-attuned physicians, theologians, psychiatrists and psychologists – with whom they had in common a positive interpretation of the powers of the human mind. Because of their fundamental differences regarding the nature of the phenomena under scrutiny, however, their shared agenda would not last very long.

A new divide

For despite their shared hopeful and positive image of the essence of human beings, the spiritualist members clung to their spiritualist hypothesis, whereas the more scientifically oriented members were more inclined to the idea of telepathy. For the latter, telepathy was more attractive than the spiritualist hypothesis since controls of measurement were easier to obtain in a telepathic experiment than during a spiritualistic séance.

Zeehandelaar had formulated his position in 1911: ‘in my opinion the spiritualist hypothesis is absolutely without proof; in the literature serious, scientific proof of identity between various so-called ‘spirits’ and dead humans had never been put forward undisputable, whatever the spiritualists may say’.75 The spiritualist members, on the other hand, believed that the psychical researchers with their inhumane demands of the mediums did not understand the precarious character of spiritual manifestations. As a result, the Dutch SPR quite quickly became the stage of fighting and bickering, reminiscent of the period before the First World War. In an example hereof, we encounter the family Cort van der Linden.

The prime minister during the First World War, P.W.A. Cort van der Linden, had been one of the first Dutch members of the British SPR.76 He seemed to have transferred this interest to his son P.W.J.H. Cort van der Linden who in 1921 published a letter in the Mededeelingen der Studievereeniging voor Psychical Research, stating quite coherently his views upon psychical research: ‘the researcher has to be critical, coldly scientific, and the ‘sensitives’ are, if I may say so, the guinea pigs’.77 This outraged the spiritualists, since like in the case of Susanna Harris they believed this critical stance disregarded the sensitive, spiritual souls of mediums.78 Apparently, the First World War did not provide the spiritualist triumph over materialism that the spiritualists had hoped for. The revival of spiritualism, however, did not end here; spiritualism remained popular until the 1930s.79 And even when the popularity of organised spiritualism waned in more recent decades, spiritualist ideas have remained, along with their uneasy alliances with psychical researchers and parapsychologists.

Conclusion

During the First World War, Dutch spiritualists provided an answer to a very modern question: how do you ascribe meaning to a seemingly meaningless world, exemplified by a pointless war? The optimistic and clear-cut message of the Dutch spiritualists sounded appealing and added to the popularity of spiritualism, especially when churches were struggling tremendously with their stance regarding the war. To spiritualists, the First World War was the apotheosis of a disrupting and sickening materialism. Spiritualists had been anticipating some kind of catastrophe resulting from these rotten materialistic axioms for a long time and saw a legitimisation of their viewpoints in the First World War. Dutch spiritualists had been firm believers in a spiritual evolution: no matter how slow humanity evolved, eventually a better day would come. In this regard, the war provided the opportunity to wipe out materialism once and for all. Dutch spiritualists therefore unanimously called for active protests against the war. Such a united stance was very welcome for spiritualists themselves as well: having experienced a devastating debate in April of 1914 about Susanna Harris’ supposed fraud, Dutch spiritualists could use a cause to fight for together. The First World War provided just that and helped the spiritualists to improve their public reputation.

Before the outbreak of the First World War, Dutch spiritualism was dominated by ideologically oriented spiritualists over critically oriented ones. This is exemplified by the shutting out of a critical spiritualist like De Fremery following the Harris incident. During World War I the dominance of ideologically oriented spiritualists – like Van Broekhoven, Beversluis and Kuijper van Harpen – continued in their expression of the abovementioned ideas. When the First World War ended, both ideologically oriented spiritualists and their critical counterparts supported the founding of the first society for Dutch psychical research. There was a shared sentiment that, after all the catastrophes that had been endured, a science was needed to demonstrate the profound spiritual character of our souls.

The first 24 members of the board of the Dutch SPR shared a hopeful and optimistic view of the human ‘soul’, whether understood in Jungian psychoanalytical terms, in psychomonistic concepts, or in spiritualistic thought. They also shared the conviction that they could scientifically prove the hidden powers of the human mind. Soon, however, familiar discussions regarding the nature of appropriate research methods and correct handling of research subjects re-emerged. It was only during the aftermath of the First World War that ideologically oriented spiritualists were aligned for the first time with more critically attuned scholars and Dutch psychical research could emerge. This peaceful alignment proved to be a temporary state, however, and a ‘spiritual evolution’ soon seemed as far away as it had ever been.